Beneath the Capitol's magnificent dome, the day-to-day business of American democracy takes place: senators and representatives debate, coax, cajole, and ultimately determine the law of the land. For many visitors, the Capitol is the most exhilarating experience Washington has to offer. It wins them over with a three-pronged appeal: it's the city's most impressive work of architecture; it has on display documents, art, and artifacts from 400 years of American history; and its legislative chambers are open to the public, allowing you to actually see your lawmakers at work.

Before heading to the Capitol, pay a little attention to the grounds, landscaped in the late 19th century by Frederick Law Olmsted, famed for New York City's Central Park. On these 274 acres are both the city's tamest squirrels and the highest concentration of TV news correspondents, jockeying for a good position in front of the Capitol for their "stand-ups." A few hundred feet northeast of the Capitol are two cast-iron car shelters, left from the days when horse-drawn trolleys served the Hill. Olmsted's six red-granite lamps directly east of the Capitol are worth a look, too. A small, hexagonal brick structure with shaded benches, a fountain, and a small grotto, called the Summerhouse, is a wonderful place to escape the summer heat.

The design of the building was the result of a competition held in 1792; the winner was William Thornton, a physician and amateur architect from the West Indies. With its central rotunda and dome, Thornton's Capitol is reminiscent of Rome's Pantheon. This similarity must have delighted the nation's founders, who sought inspiration from the principles of the Republic of Rome.

The cornerstone was laid by George Washington in a Masonic ceremony on September 18, 1793, and, in November 1800, both the Senate and the House of Representatives moved down from Philadelphia to occupy the first completed section: the boxlike portion between the central rotunda and today's north wing. (Efforts to find the cornerstone Washington laid have been unsuccessful; a 1991 search was conducted using a metal detector to locate the engraved plate—it was not found. The location may be under the southeast corner of what is today National Statuary Hall.) By 1807, the House wing had been completed, just to the south of what's now the domed center, and a covered wooden walkway joined the two wings.

The "Congress House" grew slowly and suffered a grave setback on August 24, 1814, when British troops led by Sir Alexander Cockburn marched on Washington and set fire to the Capitol, the White House, and numerous other government buildings. (Cockburn reportedly stood on the House speaker's chair and asked his men, "Shall this harbor of Yankee democracy be burned?" The question was rhetorical; the building was torched.) The wooden walkway was destroyed, and the two wings gutted, but the exterior structure was left standing thanks to Architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe's use of fireproof building materials. Congress debated moving the Capitol to another location, but in 1815 it authorized President Madison to borrow from local banks to rebuild, on their existing sites, the Capitol, White House, and cabinet quarters. Latrobe supervised the rebuilding of the original Capitol, adding American touches such as the corncob-and-tobacco-leaf capitals to columns in the east entrance of the Senate wing. He was followed by Boston-born Charles Bulfinch, and, in 1826, the Capitol, its low wooden dome sheathed in copper, was finished.

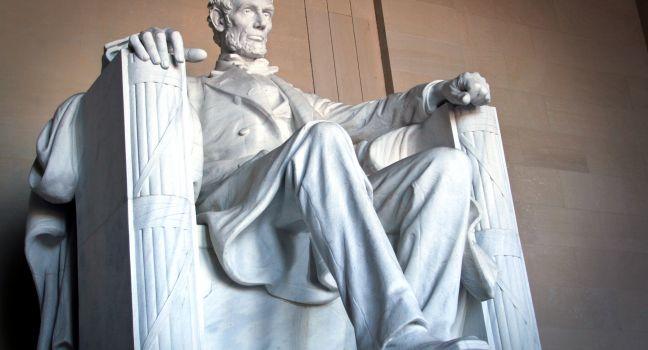

North and south wings were added in the 1850s and 1860s to accommodate a growing government trying to keep pace with a growing country. The elongated edifice extended farther north and south than Thornton had planned, and, in 1855, to keep the scale correct, work began on a taller, cast-iron dome. President Lincoln was criticized for continuing this expensive project while the country was in the throes of the Civil War, but he called the construction "a sign we intend the Union shall go on." This twin-shell dome, a marvel of 19th-century engineering, rises 288 feet above the ground and weighs 4,500 tons. It expands and contracts up to 4½ inches a day, depending on the outside temperature. The allegorical figure atop the dome, often mistaken for Pocahontas, is called Freedom. Sculptor Thomas Crawford had first planned for the 19½-foot-tall bronze statue to wear the cloth liberty cap of a freed Roman slave, but Southern lawmakers, led by Jefferson Davis (who was Secretary of War and in charge of the Capitol construction), objected. An "American" headdress composed of a star-encircled helmet surmounted with an eagle's head and feathers was substituted. A light just below the statue burns whenever Congress is in session at night.

The Capitol has continued to grow. Between 1959 and 1962, the east front was extended 32 feet, creating 90 new rooms. Preservationists have fought to keep the west front from being extended because it's the last remaining section of the Capitol's original facade. A compromise was reached in 1983, when it was agreed that the facade's crumbling sandstone blocks would simply be replaced with stronger limestone.

Free gallery passes to watch the House or Senate in session can be obtained only from your representative's or senator's office; both chambers are open to the public when either body is in session. In addition, the House Gallery is open 9 am to 4:15 pm weekdays when the House is not in session. International visitors may request gallery passes from the House or Senate appointment desks on the upper level of the visitor center. Your representative's or senator's office may also arrange for a staff member to give you a tour of the Capitol or set you up with a time for a Capitol Guide Service Tour. When they're in session, some members even have time set aside to meet with constituents. You can link to the home page of your representative or senators at www.house.gov and www.senate.gov.

Free reservations are required to visit the Capitol. They can be made through either the Capitol Visitor Center website or through the office of your representative or senators. Only those with tour reservations may enter the Capitol Visitor Center; allow time to go through security. Bags can be no larger than 18 inches wide, 14 inches high, and 8½ inches deep, and other possessions you can bring into the building are strictly limited. (The full list of prohibited items is posted at www.visitthecapitol.gov.) There are no facilities for leaving personal belongings, but you can check your coat. If you're planning a visit, check the status of tours and access; security measures may change. Note that only those with tour reservations may enter the Capitol Visitor Center.