In Istanbul, Baldwin was the writer he wanted to be. In America, he was the activist he had to be.

Experiencing Istanbul, as writer James Baldwin once knew it, takes a dash of literary imagination. First-person was a perspective that Baldwin knew well, as his writing bristles with intimacy. And much of his literary and essayistic work was discreetly inspired by Turkey’s fast-changing metropolis, preserving many of the places that buoyed his spirits for a decade.

More than sixty years after his arrival to the shores of the Bosphorus, it is still possible to retrace Baldwin’s footsteps, seeing faded fragments of the Istanbul he once knew. Here, Baldwin sought respite from the racial politics and rampant homophobia he’d left behind in the States. It was here, after the suicide of a friend and the promise of the rising civil rights movement, Baldwin regained his humanity. Istanbul was a place where he could simply be, where his profile as a queer Black author was not so etched in the national consciousness.

To understand Istanbul’s influence on this generation-defining writer—and to even plan a Baldwin-inspired walking tour of your own—read on.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Finding Traces of Baldwin in Istanbul’s Culture

In 2019, the Istanbul Biennial screened Sedat Pakay’s documentary, “From Another Place,” as part of an exhibition by the Black American artist Glenn Ligon, held on the Prince Islands. Pakay’s film featured music by Sonny Sharrock (and sung by his wife, Linda), who Baldwin chanced upon in the city. It flashes with moving images of Baldwin smiling, sharing wordless teas with local Turks, surveying the Bosphorus coast from a thin rowboat, and, in public squares, getting stares from neighborhood folks who endearingly referred to him as “Arab Jimmy.”

To Baldwin, however, Istanbul was not a one-time destination. Rather, the megalopolis was a place where he found respite from the suffocating racial politics of the West from 1961 to 1971. Istanbul offered silence, and loneliness, the very lifeblood of a writer. On the other hand, he could not hide in America and Western Europe, whether caught on a Parisian boulevard to speak for Terence Dixon’s 1970 documentary, “Meeting the Man,” or debating white intellectuals in front of the American and British public.

In Istanbul, Baldwin was the writer he wanted to be. In America, he was the activist he had to be. The two are essential to the whole, as the poet CJ Suitt mused when introducing scholar Dr. Magdalena Zaborowska, author of “James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile.” Zaborowska’s book, published in 2009, details an evergreen roadmap for literary travelers up for a trip to Turkey. Along the way, it is possible to see how some of the most important writing in America’s civil rights literature resulted from one man’s search for personal privacy and human dignity in self-imposed exile outside the U.S.

While the FBI collated nearly two thousand documents investigating Baldwin’s solidarity with Black resistance, his ambiguous sexuality, and leftist politics, the already-famous writer was abroad in Istanbul.

Where Baldwin Found Peace and Inspiration in Turkey

Zaborowska argues that Baldwin’s best-known book, The Fire Next Time, integrates what she called “Turkish folk wisdom.” Although the book is deeply American in its comments on race relations, its interfaith discussion between Islam and Christianity had ample resonance for Baldwin as he confronted Turkey’s histories of religious diversity, ethnocentric secularism, and post-imperial multiculturalism.

Essential to an understanding of Baldwin’s Istanbul is the traditional interior of a Turkish home, complete with a maid serving numerous breakfast dishes and bottomless samovars of tea. Such moments are revealed in the outtakes of Pakay’s documentary, in which Baldwin has drawn his curtains and is fully dressed, spreads jam on his bread, peels a hard-boiled egg, and sits alone, worlds away from the FBI and segregationists.

At times, Baldwin would stay in on cold Istanbul nights and fry catfish, Southern-style, with a flower-print apron tied around his waist. He was not the heteronormative male leader America’s white, liberal establishment expected of him. Their politicians and intellectuals sought to exploit his fame to bridge increasingly disillusioned Black constituencies. In the spirit of conscientious objection, Baldwin dodged the draft of America’s deadly race war to pursue his art and listen to his own voice.

In October 2022, Christie’s auctioned a never-before-seen Beauford Delaney portrait of Baldwin beside one of Gülriz Sururi, his first host in Istanbul. As a budding writer in New York, Delaney was like a father to Baldwin, and their time in Istanbul nurtured their familial and artistic relationship. In the 1966 portrait, Baldwin appears docile and child-like, his hands relaxed over his legs with Istanbul’s skyline behind him.

Retracing Baldwin’s Footsteps Today

Today, there are myriad ways a traveler can retrace Baldwin’s footsteps. You could start by going to Istanbul’s Taksim Square, where Baldwin arrived in Istanbul one stormy night with an unfinished manuscript tucked under his arm. If you were Baldwin, you would crash a wedding party on your first evening and meet actors, artists, and intellectuals. Like him, you might fall asleep on someone’s lap to the sound of Turkish conversation. You might stroll along the bustling Istiklal Avenue, where Baldwin walked to the city’s storied European districts, stopping for a coffee at Pera Palace Hotel, where Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, and Agatha Christie stayed.

You can saunter through alleys under the bay windows of old Greek family houses that were smashed up in the Istanbul riots in September 1955, when Turkish nationalists committed acts of genocide against Turkey’s Greek minority. For a quieter walk, Baldwin ambled along the forested coasts of the Bosphorus strait, where a room in the waterfront mansion of Ahmed Vefik Pasha awaited his stay in a room beside its prolific library. You can dine as he did at meyhane fish restaurants where stars like Marlon Brando once sat by his side, sipping aniseed liquor. Or, you can frequent the theater districts and drag clubs by the haunts of Cihangir, beloved by ex-pats, before strolling uphill past the castle-lined hills of the Rumeli Fortress, where medieval Turks besieged Constantinople.

You could drink wine with academicians like John Freely at Robert College, now the verdant campus of Bosphorus University, one of the last bastions of Turkey’s democratic activism, or return downtown to the Levantine districts whose turn-of-the-century architecture evokes Lower Manhattan’s tenements. Their storied buildings overlook the Golden Horn on either end of the Galata Bridge, from the art cafes of Beyoglu to the caravanserai inns of Byzantine Fatih, where greetings in Italian, French, and Ladino are exchanged among fishers mixing idioms in Turkish, Arabic, and Persian about the late Ottoman capital.

Turn through the narrow alleys to Sultanahmet Square, and meditate on Muslim prayer inside the recently renovated Blue Mosque, where Baldwin once posed for a photo. Its intricate patterns glow along massive pillars, more complex than one pair of eyeballs can hope to fathom across the glimmering, domed ceiling.

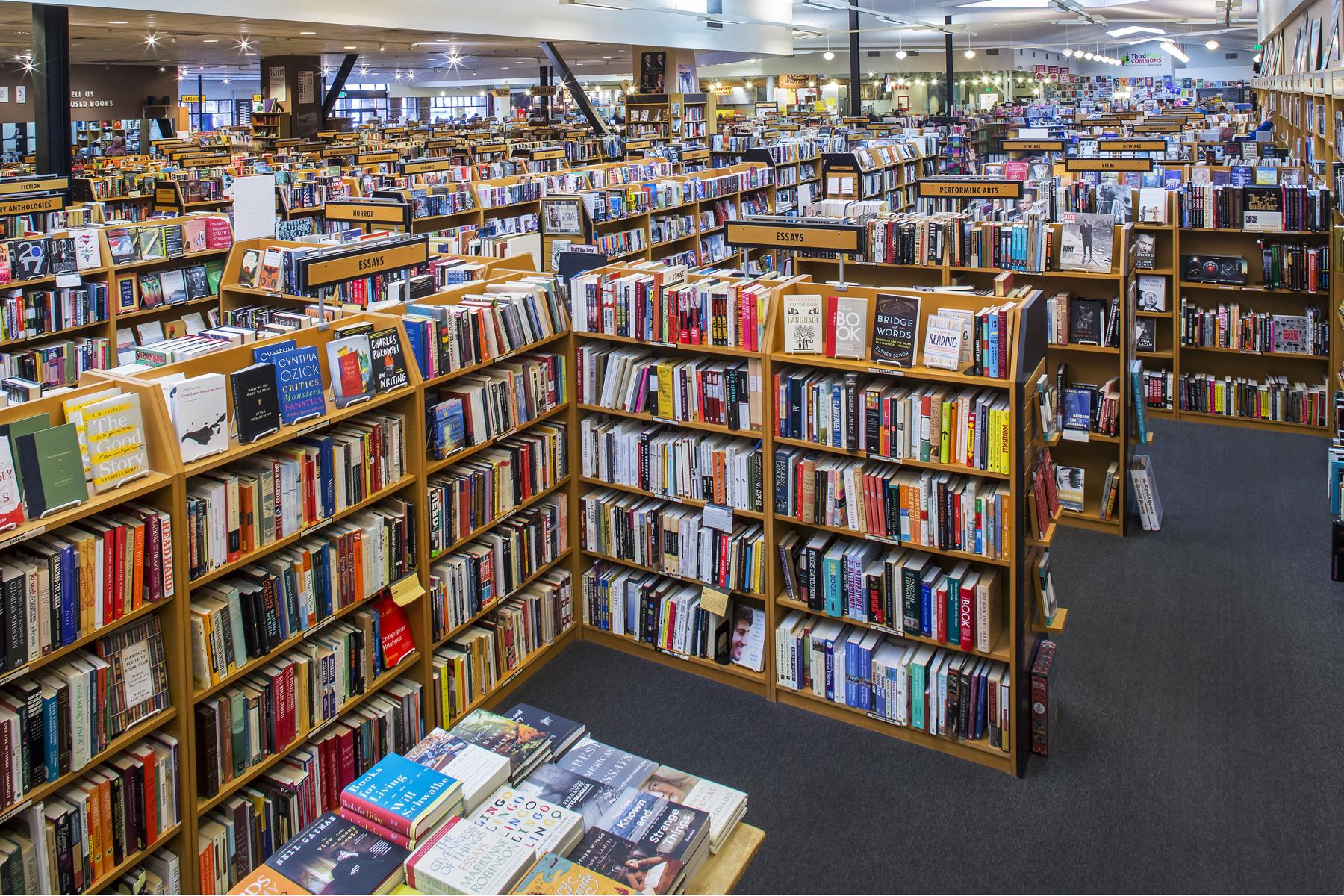

Amid the bazaar of second-hand bookshops around the corner—named after Istanbul’s second sultan, Beyazid II—find a Turkish translation of Another Country, which Baldwin completed in Istanbul in 1961. Here, he found himself ten years later, shooting the documentary, “From Another Place,” by Turkish filmmaker Sedat Pakay. In the film, he smiles, holding up the Turkish translation of his book. Baldwin—and his literature—found a second home in Istanbul.